【by Jau-lan Guo, June 2021】

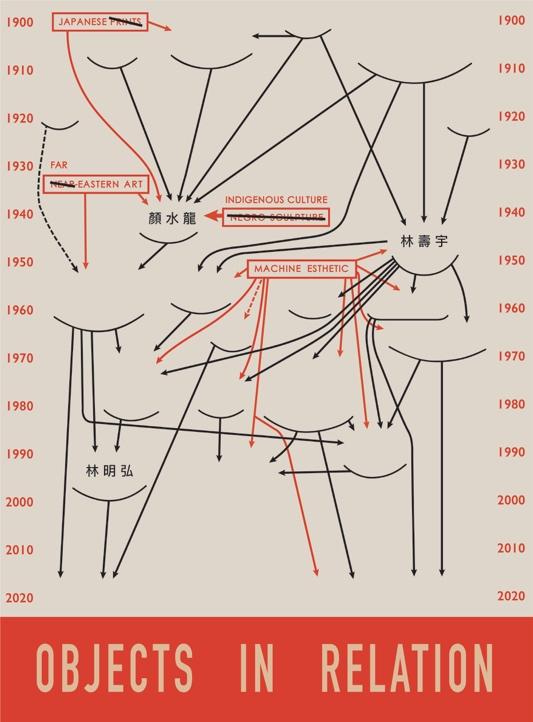

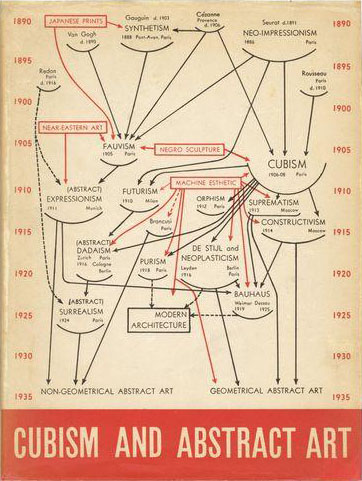

The following diagram, “Objects in Relation” [Fig. 1] was created for the exhibition On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time, it was created through an alteration process that is illustrated by comparison with its original, “Cubism and Abstract Art” [Fig. 2]. On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time is a collaborative exhibition involving two historical Taiwanese artists, Yen Shui-long, and Richard Lin; two curators with backgrounds in art history, Lee Ambrozy and myself; and the contemporary artist Michael Lin. It is currently on display at the Museum of National Taipei University of Education (MoNTUE).

Diagramming “Objects in Relation”

In 1936, Alfred Barr drafted “Cubism and Abstract Art” [Fig. 2], which attempted to use a two-dimensional diagrammatic format to explain an evolution from post-impressionism to abstract painting. It represents a conception of modernist world art that constructed its narrative through the institutional collections and exhibitions of the MoMA in New York. My draft, “Objects in Relation” [Fig. 1], attempts to establish a new relationship between the practices of the three artists in this exhibition and Barr’s diagram symbolizing “modernist world art.”

My adaption, “Objects in Relation” [Fig. 1], firstly removes the names of the various art schools Barr used as parameters, and retains the red arrows indicating flow and the relationships of Modern Art to non-Western elements: Japanese prints, Far-Eastern Art, “Negro Sculpture,” Machine Aesthetics, etc. In Barr’s original diagram, these elements were regarded as mere sources of inspiration for elite artists––for example, African art for Cubists or Japanese prints for the Fauves––but these relationships were not the primary concern of the original chart’s dynamics. Other alterations to “Objects in Relation” include deleting the word “print” after “Japanese,” changing the “near” of “Near Eastern Art” to “Far,” and turning “Negro sculpture” into “Aboriginal Culture.” Although it has been revamped, Barr’s graphic structure remains a fundamental part of this new version of the art narrative. It speaks to the artistic practices and pursuits of the three artists in the exhibition, and through its adaptation, the diagram helps explain the relative relationship between their art practice and world art, placing them against the background of world art history and implying a new, non-binary relationship between the three.

The relationships of Yen Shui-long to Bauhaus; to Japanese craft master Yanagi Sōetsu, and to aboriginal cultures; of Richard Lin to Chuang Tzu’s philosophy, Constructivism, or machine aesthetics; of Michael Lin to Relational Aesthetics and the emergence of global contemporary art at the end of the 1990s––the act of altering Barr’s diagram is a way to help us to reconnect the axes of Taiwanese art history with world art history. And lastly, the life spans of these three artists Yen Shui-long (1903–1997), Richard Lin (1933–2011), and Michael Lin (1964–) determine the temporal axes on both sides, and can be inserted back into the chart in chronological order. The gesture of transforming Barr’s chart, as an act of constructing the Taiwanese art history, seems to provide us with a concrete object for dialogue.

Whether or not a unified world art history exists is an open question; even so-called “global art history,” as Hans Belting has commented, is perhaps only a phenomenon whose premise is determined by international circulation and flow. The focus of this new art historical diagram on issues of circulation and relationships is not only describing human movement, but the dissemination of artistic concepts as well.

Writing Taiwanese Art History through Exhibitions

Similar to circumstances prevalent in most Southeast Asian nations, art history in Taiwan is inextricably linked to the construction and advocacy of national identity. Perhaps this is not a bad thing. It provides artists with motivation to reflect on local contexts or contribute to dynamic relationships between the local and the global.

In his article “Charisma and Withdraw in Thai Contemporary Art,” David Teh used Rirkrit Tiravanija, Surasi Kusolwong, and Navin Rawanchaikul as examples of artistic practices placed in the framework of Relational Aesthetics to explore how Thainess is used as an interpretative crutch in mediating tensions between the local and the global in Thai contemporary art and how such interpretative frameworks circulated like global currencies.[1]

Installation view, On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time, MoNTUE, 2021. (Image Courtesy of MoNTUE, Photography by Chong Kok Yew)

If a bidirectional relationship of art practices involving Relational Aesthetics within the process of contemporary art’s globalization and art practices in relation to regional and global currencies is already present, and a system of shared approaches has already emerged, then On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time inverts the idealism surrounding notions of display in Relational Aesthetics to reflect on the context of local art practices.[2] The exhibition establishes a dynamic relationship that becomes a lens for examining history. Here, the display mechanisms of Relational Aesthetics are combined with the merits of conviviality to reflexively become the object of cognition,[3] engendering a transhistorical approach to our local art context that allows the people, objects, and forms of the exhibition to collectively conspire in deriving meaning through exhibition making. Could it be possible that it will not only propose revisions to regional art historical methodologies vis-à-vis world art history, but might also have a positive effect on the regional art practices which are confronted by strategies belonging to world art?

The exhibition adopts Michael Lin’s display mechanisms in reconceiving how we understand historical artists and artworks from the past. As soon as the proposal was materialized, it became a tool for cognition and an art historical object of discussion. Ideally, the ambitious exhibition interface attempted here will be inscribed in the discipline of art history as an endearing new relationship between people, objects and form. In this way, the “art” is not merely an act of making, but through the process of creating form, proposes a framework (both intellectually and physically) that allows us to reflect on art history’s methodologies.

From Art History’s Materialist Orientations to Material Culture

Conserving the material fragility of art works has long been understood as the mission of museum collections. This leads to the safeguarding of materiality, which is inevitably treated within the discipline of art history by prioritizing techniques of iconography and formal analysis. Comparing it to spiritual culture, Art historian George Kubler in 1962 proposed to extract everyday “things” as key elements in the history of human creation: “But the ‘history of things’ is intended to reunite ideas and objects under the rubric of visual forms: the term includes both artifacts and works of art, both replicas and unique examples, both tools and expressions-in short all materials worked by human hands under the guidance of connected ideas developed in temporal sequence. For all these things a shape in time emerges.”[4] Kubler here refers to material and cultural objects––things that participate in daily life. Isn’t this precisely the same standardization of materials found in Michael Lin’s work: wooden studs, wall panels, bicycles, and industrial lacquer paint? Or is this exactly what Yen Shui-long wanted to translate from artisanal woven bamboo furniture into the handicraft industry, or into the Taiyang Bakery pastry boxes? Or again, is this we see in Richard Lin’s aluminum panels and IKEA Helmer drawer units? Perhaps we can also consider the ambiguous status of the exhibition walls, the booth, or even the exhibition itself? On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time and its exhibition interface provoke questions of transhistoricity, from the standardization of materials, materials usage within art, and the re-configuration of the exhibition hall. Namely, its persistent attempts to interfere with the responsibilities conventionally ascribed to art institutions.

Genealogy and Transhistoricity

On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time is therefore an exhibition where we can observe relational objects within a specific context, where the audience is first encouraged to find horizontal connections between the works using the geometric organization of the woven bamboo furniture, the hard edges of Richard Lin’s geometric abstraction, or the standardized wooden planks of the exhibition walls and showcase displays. It might even appear to be a return to formalist aesthetics. Yet, it is on this last point that On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time and Paul Crowther’s formalist approach to images in The Transhistorical Image (2002) have a faint resonance.

Installation view, On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time, MoNTUE, 2021. (Image Courtesy of MoNTUE, Photography by Chong Kok Yew)

This is an approach of returning to artworks themselves after post-structuralism’s critique of formalist art methods, especially as post-structuralism replaced formalist art history with the social history of art that has skeptical tendencies. Unintentionally, the production of art thus becomes a product of curation, and once again curatorial approaches reflexively embrace artistic form, a strategy for rescuing the precarious (aesthetic) value of art. Here it must also be added that Crowther’s formalist methodologies and his belief in the intrinsic value of art are not based on formalist characteristics themselves, but rather on graphic images that are understood to be an embrace of the power of form. In this way, a work of art (whether it is a ready-made object, material cultural object, or abstract form) is embedded within an ever-expanding network of forms, and is more able to resonate with the forms of other works through its materiality.

From the perspective of art historical methodology, this is not the extraction of form for the purpose of discussing sociopolitical themes, but is a genealogical look at how form is envisioned, conceived, expanded, polemicized, and even expanded upon from the work itself to regional and global circulation of forms, exhibition models, and the politics of display in regional and global circulation.

An Endorsement of the Improvisational Gaze

Installation view, On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time, MoNTUE, 2021. (Image Courtesy of MoNTUE, Photography by Chong Kok Yew)

In his oscillating role between artist and curator, Michael Lin designed display structures, walls, and vitrines that make all the curatorial interventions transparent and endow the exhibition with the conditions for bi-directional discourse. The first is how the poeticism inherent in the politics of display intervenes in historical art works and our reception of them, namely, in reflections on art historical writing. And the second: when we shoulder the responsibility of interpreting historical artworks, how do we liberate them from being mere emblems of narratives that emphasize the continuity of time and return to them the contingency of their significance and value when presenting them to audiences today? In this way, the relationship between art objects and viewers, art and its environment become relevant, and the audience is encouraged to become conscious of their physical environment and location within. The man-made objects on display thus encourage an observational logic that is both processual and experience-driven.

We could say that any moment of observation belongs to the present, but this does not necessarily interfere with that moment’s relationship to history. For exhibitions of historical material, “… that relationship can only occur if the present is endorsed as the time of viewing, hence, the viewer’s responsibilities is also necessarily endorsed.”[5] If historical artworks cannot avoid becoming witnesses to the genealogical experience, and if display itself is the thread to the needle, then in the moment the audience becomes observers of a historical moment, he/she/they become actors within another piece of history.

In the past, art museums wrote art history through exhibition making. Today they have become sites of public gathering and cultural debate. The audience witnesses art events and participates in art history, all in the name of art. On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time, through its performance of the act of compilation, co-conspires with the audience in writing art history.

This is an exhibition about exhibiting, and it is also an attempt to engender encounters between curation and art history: historical art works, curators, art historians and artists have become collaborators, while the exhibition becomes an open process of knowledge production. Experimental art historiography implores the museum for narration, temporality, and methodology, and strives to create a dual mechanism capable of providing a panoramic historic view. Accordingly, an artist who devised an exhibition display mechanism became an art historian; art historians appear as art historiographers, audiences who move through the space (in their binary roles of invited, yet improvisational participants) are witnesses to it all.

(Translated by Lee Ambrozy)

* This article is based on the curatorial discourse for the exhibition On the Passage of a Few Persons through a Brief Moment in Time at MoNTUE and is sponsored by the Lim Pen-Yuan Cultural and Educational Foundation.

AUTHOR

Jau-lan Guo, Taipei National University of the Arts, Taiwan

NOTES

[1] David Teh, Thai Art Currencies of the Contemporary (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017).

[2] Relational Aesthetics was one way for the above-mentioned artists to be recognized by mainstream contemporary art in the late 1990s.

[3] On the one hand, it involves global and regional politics of display, while at the same time, it leverages a transhistorical understanding of regional art.

[4] George Kubler, The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), p. 9: “But the ‘history of things’ is intended to reunite ideas and objects under the rubric of visual forms: the term includes both artifacts and works of art, both replicas and unique examples, both tools and expressions-in short all materials worked by human hands under the guidance of connected ideas developed in temporal sequence. For all these things a shape in time emerges.” Kubler was not referring to “art objects,” but material culture.

[5] Meike Bal, “Toward a Relational Inter-Temporality,” in Eva Wittocx et al., ed., The Transhistorical Museum: Mapping the Field (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2018), p.55: “But that relationship can only occur if the present is endorsed as the time of viewing, hence, the viewer’s responsibilities is also necessarily endorsed.”