【by Kin-Long Tong, June 2023】

Throughout the last century, from the inception of the May Fourth Movement in 1919 to the Anti-Extradition protests in Hong Kong in 2019, student and youth groups have consistently emerged as a critical driving force behind the promotion of socio-political transformations. Within the Chinese context, students have been metaphorically depicted as beacons of hope in society, representing a source of optimism, innovation, and idealism. A notion vividly expressed by Chairman Mao during his renowned address to Chinese students in Moscow back in 1957 has well reflected such a belief:

The world is yours, as well as ours, but in the last analysis, it is yours. You young people, full of vigor and vitality, are in the bloom of life, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning. Our hope is placed on you. The world belongs to you. China’s future belongs to you (Mao 1957, reprinted in Mao 2020).

However, the quote’s initial status as symbol of hope was later subverted by Hong Kong’s pop culture, where it became the subject of biting satire after the disastrous failure of Cultural Revolution. Director Fruit Chan’s film Made in Hong Kong 香港製造 (1997) offers a particularly poignant example. In the last scene of the movie, the three young and marginalized protagonists meet their untimely demise and their souls are depicted playing in a cemetery. As Mao’s Moscow quotes are recited in the background, the tone shifts to one of dark humor, evoking a sense of ironic detachment and disillusionment.

The contradictory and contested representations of young students in Hong Kong have been articulated and circulated through political discourses. In the Netflix documentary film Joshua: Teenager vs. Superpower (2017), Joshua Wong and his Scholarism comrades were celebrated as a modern-day David, bravely standing up to the oppressive forces of authoritarianism. However, this heroic image is often contrasted with a more negative portrayal of Wong and his peers as misguided and naive, serving as a “US puppet” who “would just probably read out the speech prepared by his political mentors to badmouth Hong Kong” (Kwok 2019). Hong Kong’s young students have been plagued by a recurring cycle of melancholy that spans multiple generations and political orientations, from the Chinese nationalists who participated in the 1967 Leftist Riots to the pro-liberal activists who took part in the 2019 Anti-Extradition protests. This pervasive sense of disillusionment was captured by the documentary film Blue Island (2022), which highlights the deep-seated sense of in-betweenness that characterizes the experiences of Hong Kong’s young people in a world shaped by powerful global forces beyond their control.

As a Hong Konger, an international student currently based in London, a print culture researcher, and an observer of student activism, I am often confronted with the challenge of reconciling the complex and often contradictory perceptions – the label of “hopes and despairs” – attached to students.

Democratic Vanguard or Fragile Bodies?

The complex representations of students can be conceptualized through sociological languages. The identity of students is a unique construct that defies more rigid forms of social cleavages such as class and race. The concept of “studenthood” is inherently transient in nature (Hussey and Smith 2010), as individuals move through various phases of learning and development en route to graduation. This fluidity can be powerful, as Weiss et al. (2012: 11) theorize students as a group of people occupying “a distinct, transitional niche,” where they can be free from the constraints of more demanding adult responsibilities. The academic setting provides students with a fertile ground for the acquisition of modern ideas and knowledge, as universities and school communities serve as hubs of intellectual exchange and innovation. In her analysis of China’s late 19th-century modernization efforts, Alice Ngai-ha Ng Lun (1981: 181) cites a famous address by Dr. Sun Yat-sen to Li Hung-Chang,

I have obtained a British medical degree from Hong Kong…I paid, however, special attention to their (Western) ways of building up a wealthy nation and a powerful army, and to their laws for social reforms. I also discerned the essentials of current events and changes, and the means of maintaining peaceful relationship with other countries. (Sun 1894)

Throughout history, similar stories have occurred where students have encountered enlightening moments during their education and emerged as influential leaders in society. In the Asian context, students are often imagined as future intellectual elites, empowered with cultural capital and imbued with the potential to become powerful agents of change and progress (Altbach 1982).

If students are often described as “vanguard actors in turbulent times” (Johnston 2019: 55), student publications would be their tips of spear that point a path towards a glimpse of radical hope. Their publications can be contextualized within the wider trend of alternative media, and historicized with its roots in century-old print activism (Schreiber 2016). Throughout the local history of Hong Kong, student-activists have actively produced various forms of publications, including periodicals and non-standardized zines, to amplify non-mainstream narratives, mobilize support, and engage with the public (Pan 2022). Youth publishing can be seen as part of the “counter-public sphere,” which challenged great powers’ discourses through its multifaceted inclusivity, accommodating diverse worldviews and subjectivities and nurturing social activism in undemocratic societies (Cheng 2021). Publications function as contentious and living archives that retain remnants of past resistance, yet to be unlocked in the future. This is exemplified by the actions of those who risked their lives to save and send student-activist leaflets abroad during and after the June Fourth Incident in Tiananmen Square (Bond 1991). Moreover, alternative publications played a critical role in fostering an affective community among movement supporters and protesters, allowing them to engage in self- and communal care while resisting state violence (Yam and Ma 2023).

Nonetheless, the fragility of students may be at risk of being lost in translation as their real-life complexities are distilled into academic language – theorization often entails a tendency towards generalization. In fact, schools can serve as sites of control during protests, whereby students are subject to school rules and other kind of disciplinary and socialization measures. Campus and publications can be censored by the regulatory regimes inherited from the colonial government and the newly imposed National Security Law (Baehr 2022). This was evident during the Anti-Extradition protests; from June 2019 to January 2020, more than 1,000 young people under the age of 18 were arrested during the Anti-Extradition protests (Barron 2020). Pinner (1971) argues that students are “marginal elite in politics.” Due to their lack of effective means of coercion, most political alliances involving student movements are short-lived and students are often deprived of the benefits of victory, and may also become targets of repression following defeat. In my eyes, there exist two works of emotional death that have the capacity to capture the intricate inner lives of student activists. The first one is Lost in the Fumes地厚天高 (2017), a documentary film of the localist leader Edward Leung, who was also a student at the HKU. While Leung has been perceived by viewers as a spiritual leader in the Anti-Extradition protests due to his imprisonment for his involvement in the 2016 Fishball riots, the film also reveals the more vulnerable and human aspects of Leung’s personality, including his tendencies towards laziness, escapism, and a yearning for a normal social life. The second work is Beneath the Skies 天空下 (2020), an anthology published by CUHK Records山城記事documenting the lives of CUHK community during and after the Anti-Extradition protests. The collection not only includes the stories of students taking to the protest frontlines and supporting one another, but also the struggle with PTSD, the anguish of separation, and the uncertainty about future.

A Digital Humanities Inquiry, A Transnational Dialogue

To traverse this paradox of hope and despair, I believe we can delve into the annals of history, where cataclysmic events unfolded, shaking the very essence of students’ subjectivity and illuminating the true meaning of hope. During my pursuit of a master’s degree in archives and records management at UCL in 2021, I had the opportunity to curate a mini online exhibition with the support of UCL Special Collections. The focus of my analysis was on the UCL student magazine “New Phineas” in 1943, a time when the devastating effects of WWII, which claimed the lives of 70 million people, continued to reverberate throughout the world. Between 1940 and 1941, London was subjected to intense bombing by Nazi Germany, known as “The Blitz,” resulting in severe damage to the UCL campus and the relocation of departments to various parts of Britain. “New Phineas,” managed and contributed to by UCL students, offers a unique glimpse into the mundane aspects of life during WWII, which are often overshadowed by the grand narrative of war history. I am intrigued by the lives of UCL students during such a tumultuous period, marked by one of the most catastrophic pages in human history.

With the help of optical character recognition techniques, I can easily import digitized materials to computers for content analysis. I strive to embrace a more digital humanities approach, specifically employing text mining techniques that enable the transformation of text into an intermediate form of “textual databases.” From these databases, it is argued that researchers can extract patterns and knowledge. I did not give much thought to selecting this method, as it appeared to be a more scientific means of evaluating the materials, and digital humanities is the trend. Alternatively, perhaps I chose it because I could not bear the emotional weight of the text. During the text preprocessing stage, I removed stop-words, punctuations, and numeric characters. Additionally, I applied lemmatization to the words in the text, which restored them to their original form in the dictionary. However, paradoxically, the act of reducing words to their base form sometimes renders the text unrecognizable, as it removes words from their sentence context.

However, datafication can still offer a new approach to interpreting text in many occasions. In the course of conducting a term frequency analysis, I made a startling discovery: the word “hope” appeared with greater frequency (n=64) than the word “war” (n=61). My mind is immediately filled with a series of questions: What were the students hoping for? What allowed them to hold onto hope during the bleakest chapters of human history? And what precisely did their notion of hope entail? Given the small sample size, I was managed to conduct a manual check of the word “hope” using a rudimentary method of “command + F.” Suddenly, the keyword analysis project takes on a new dimension, deviating from its association with digital humanities, and instead aligns more with the ideas presented in Raymond Williams’s seminal book, Keywords (1976). This work meticulously traces and elucidates the evolution of the meanings of 109 individual words throughout history. In doing so, Williams not only sheds light on the affective and analytical power of keywords but also highlights the politically contested nature of meanings embedded within the lexicon of language.

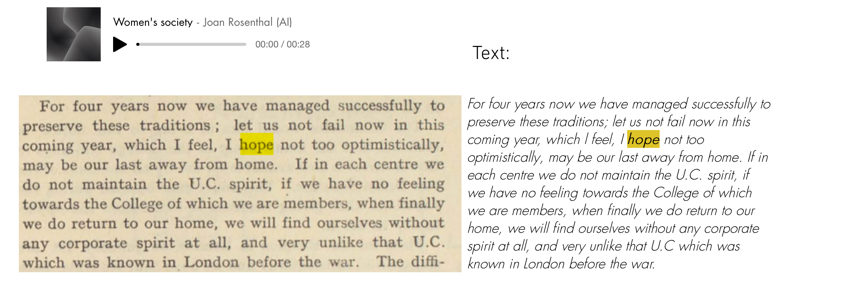

I tried to visualize the outcome by curating a selection of items from UCL Student Magazines, ‘New Phineas’, and created an online exhibition entitled “Hopes in the Darkness.” This exhibition features a diverse range of historical artifacts, including drawings, photographs, poems, and articles. On occasions, hope is regarded as interchangeable with “perseverance,” as individuals maintain the aspiration that their unwavering determination will lead them back to their homeland. One of my favorite quotes comes from the annual address given by Joan Rosenthal, President of UCL Women’s Union Society in autumn 1943:

For four years now we have managed successfully to preserve these traditions; let us not fail now in this coming year, which l feel, I hope not too optimistically, may be our last away from home. If in each centre we do not maintain the U.C. spirit, if we have no feeling towards the College of which we are members, when finally we do return to our home, we will find ourselves without any corporate spirit at all, and very unlike that U.C which was known in London before the war.

(New Phineas Autumn 1943, p. 17)

Picture 1: Part of the Exhibition

Picture 2: Joan Rosenthal’s speech

However, it appears that for many younger individuals, particularly those in their late teens to early twenties, their deepest hopes revolve around social events. In a snippet of college news published in the summer issue of New Phineas in 1943, there was a report of a successful social event held by U.C.L. women in Aberystwyth:

There is little to report from Aberystwyth, the term, having only just started. There is in fact only one social event to be mentioned, a very successful social in King’s Hall, given by the U.C.L. women in Aberystwyth; let us hope it is only the first of many. (New Phineas Summer, p. 11 1943).

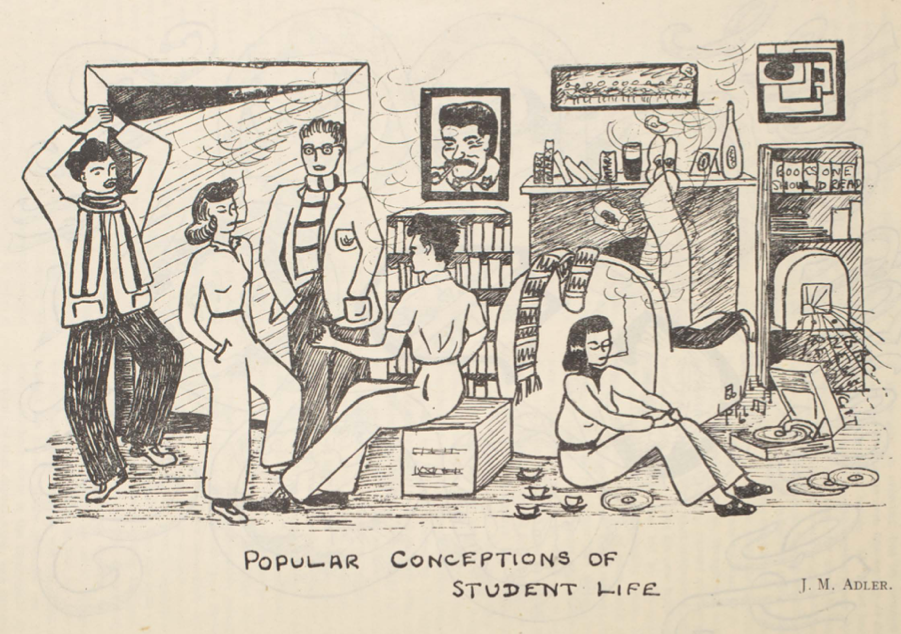

During World War II, a number of UCL Departments, including that of J. M. Adler, were relocated to Aberystwyth, where Adler served as a member of the Union Society. Adler’s cartoon entitled “Popular Conceptions of Student Life” was attached to the college news, serving as a visual representation of the students’ longing for a return to normalcy and social life. In the cartoon, the friends lazily lounge around the room, enveloped in a cloud of smoke as they chat and unwind. The room is warm, so people put off their scarves. Empty bottles litter the room, a testament to the merriment that had taken place. The strains of music fill the air, lending a sense of carefree joy to the scene. In one corner of the room, a small bookshelf bears the inscription “Books one should read,” a reminder of the importance of literature in their lives. The horrors of war seem distant and removed from this haven of calm and camaraderie.

Picture 3: A Cartoon titled “Popular Conceptions of Student Life”

Source: New Phineas Summer 1943, p. 10, illustrated by J. M. Adler.

From Beneath the Skies 天空下 to the New Phineas 1943, I can see that student publication are “object of hopes.” This is not because of the transitional niche of students or the progressive affordances of student publications, but rather due to the intrinsic communicative power of media that can transcend temporal and geographical barriers. The essence of radical hope lies in the belief that, no matter the medium in which our thoughts are captured – be it yellowed pages in dusty library archives or NFT tokens on the blockchain – someone, somewhere and at some point in time, others may come to comprehend the fundamental aspirations that propel us forward. Whether it be an impassioned activist, a diligent historian, or even a casual observer employing digital humanities techniques to decode old texts, the possibility of our intentions being understood offers a glimmer of hope in a world that can often seem uncertain and bleak, and where the interpretation of meaning is heavily contested.

AUTHOR

Kin-Long Tong, PhD Candidate, Department of Information Studies, University College London, UK

REFERENCES

Altbach, Philip. 1982. Higher Education in the Third World: Themes and Variations. Singapore: Maruzen Asia.

Baehr, Peter. 2022. Hong Kong Universities in the Shadow of the National Security Law. Society 59: 225-239.

Barron, Laignee. 2020/01/22. ‘I Absolutely Will Not Back Down.’ Meet the Young People at the Heart of Hong Kong’s Rebellion. Time Magazine, https://time.com/longform/hong-kong-portraits/.

Bond, Sherry. 1991. An Archive of the 1989 Chinese Prodemocracy Movement. The British Library Journal 17(2): 190–197.

Cheng, Edmund W. 2021. Loyalist, Dissenter and Cosmopolite: The Sociocultural Origins of a Counter-public Sphere in Colonial Hong Kong. The China Quarterly 246: 374-399.

CUHK Records 山城記事. 2020. Beneath the Skies [天空下:中大人反送中運動訪談集]。Hong Kong: CUHK Records山城記事.

Hussey, Trevor., and Patrick Smith. 2010. Transitions in Higher Education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 47(2): 155–164.

Johnston, Hank. 2019. The Elephant in the Room: Youth, Cognition, and Student Groups in Mass Social Movements. Societies 9(3): 55.

Kwok, Tony. 2019/09/22. Joshua Wong, a US Puppet and Traitor to His Country. China Daily, https://www.chinadailyhk.com/articles/244/25/159/1569148927554.html.

Mao, Tse-Tung. 2020. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung/The Little Red Book. London: Pattern Books

Ng Lun, Alice Ngai-ha. 1981. The Hong Kong Origins of Dr. Sun Yat-Sen’s Address to Li Hung-Chang. Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 21: 168-178.

Pan, Lu. 2022. New Left without Old Left: The 70’s Biweekly and Youth Activism in 1970s Hong Kong. Modern China 48(5): 1080 – 1112.

Pinner, Frank A. 1971. Students-A Marginal Elite in Politics. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 395: 127-138.

Schreiber, Rachel. 2013. Modern Print Activism in the United States. Farnham: Ashgate.

Williams, Raymond. 1976. Keywords: a Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London: Croom Helm.

Yam, Shui-yin Sharon and Carissa Ma. 2023. Being Water: Protest Zines and the Politics of Care in Hong Kong. Cultural Studies https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2023.2191123